Barriers and facilitators to maternal healthcare in East Africa: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis of perspectives from women, their families, healthcare providers, and key stakeholders | BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

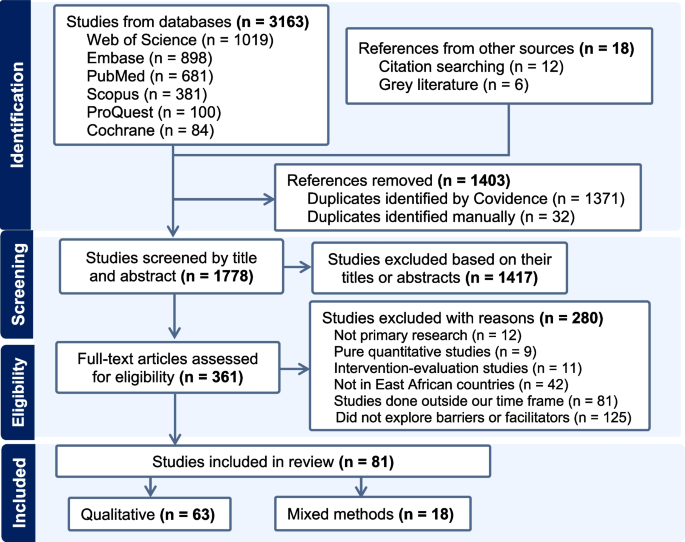

Study selection

Overall, 3163 references were initially located through searching the databases, and an additional 18 were located through other sources such as checking the reference lists of located papers. After the exclusion of duplicates, 1778 remained, of which 361 were retrieved for full-text review. Of these, 280 studies were excluded for reasons such as intervention-evaluation studies, the country of study being outside East Africa, studies done outside our time frame, and having primary outcomes that did not explore barriers or facilitators. A total of 81 studeies was retained for further analysis [Fig. 1].

Flow chart of the selection process for eligible studies

Characteristics of the included studies

Despite a thorough search of all included East African countries, no eligible studies were identified for Burundi, Comoros, Djibouti, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, and Sudan. This suggests that up-to-date evidence on this topic is lacking for a large part of the East African countries. Nearly half (48%) of the reviewed studies originated from Ethiopia. Of all the studies included, 67% aimed to explore only barriers. Meanwhile, 32% focused on SDC, and only 7% were concentrated in PNC [Table 2].

Summary of methods and participants in included studies

Most included studies (78%) used an exclusively qualitative approach, and 22% employed mixed methods. Among the eligible studies, 90% involved care recipients, such as women of childbearing age, pregnant women, or postpartum women; and 30% involved the families of care recipients, such as husbands, heads of households, mothers, or fathers-in-law. In terms of sample size, 27% of studies involved 21–40 participants. Data were collected through interviews and FGDs in 47% of the reviewed studies. Also, 71% of the included studies employed thematic analysis [Table 3].

Quality appraisal results

The CASP quality appraisal tool was employed to assess the included studies, identifying potential research limitations based on ten specific criteria. The majority of the studies demonstrated moderate to good quality. Notably, all 81 included studies presented a clear statement of their research aims. However, 13 studies failed to explicitly describe the research design employed to address these aims, and 22 studies did not adequately report the relationship between researchers and participants. To address these gaps, the research team adopted an inclusive approach to critical appraisal, which allowed for a comprehensive understanding of each study’s strengths and limitations. This in-depth evaluation enhanced the reliability of the findings while ensuring a more thorough interpretation of the data. Detailed scoring for each domain of the included studies is available in Additional File 4.

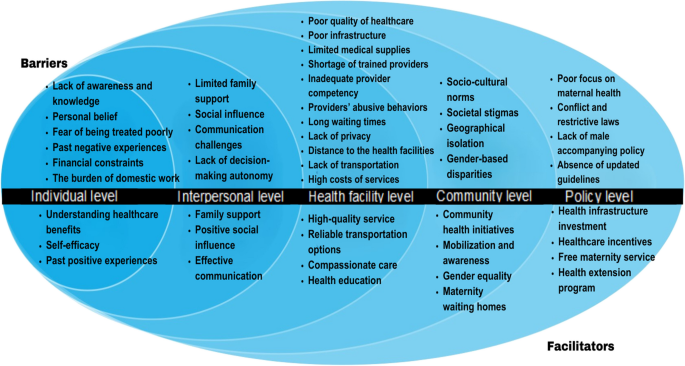

Barriers to maternal healthcare

Of the 81 studies included in this synthesis, 76 described barriers to accessing the maternal healthcare from the perspectives of care recipients, their families, healthcare providers, and/or key stakeholders. Below, we discuss these barriers according to the socioecological level at which the barrier occurs [Table 4 and Fig. 2].

Summary of the findings using a socio-ecological framework for a qualitative evidence synthesis of barriers and facilitators to accessing the maternal healthcare in East Africa

Individual level barriers (n = 55)

Lack of awareness and knowledge

Of the 55 studies reporting individual level barriers, 28 indicated that a key barrier to accessing maternal care is lack of awareness and knowledge about maternal health issues and the importance of utilizing maternity care services [16, 25, 28, 29, 31, 34, 37, 49, 53, 55,56,57,58, 60, 61, 64, 67, 71, 73, 77, 80, 81, 86, 92, 96, 99,100,101]. These studies also highlighted that a lack of knowledge led to hesitation in seeking maternal health services [16, 37, 49, 86, 100]. A healthcare provider from Kampala, Uganda, made the following remark during an interview:

“The challenge we face is that most of these women are not aware, they come in when most of them didn’t go for antenatal, and they do not know the importance of going to a health center for ANC. […] at delivery and they come at the last minute… she is a prime gravida (first-time pregnancy), she doesn’t know that this height was going to be operated […] some of them, they do not do scans, you find that even if the baby is in the wrong position but for her, she is saying that I have to push” [100].

Personal beliefs

A total of 21 studies indicated that personal beliefs affected women’s utilization of maternal healthcare, often leading them to delay or avoid care altogether [19, 25, 26, 34, 49, 50, 53, 55, 56, 62, 63, 65, 68, 70, 73, 86, 88, 96, 98, 99, 103]. These studies noted that participants believed the absence of abnormal symptoms during pregnancy reflected the normality of the fetus, which hindered them from using maternal care [19, 26, 49, 70, 88, 99]. A 32-years-old Ethiopian woman shared her beliefs as follows:

“ . . . All of my previous pregnancies, as well as this one, have gone smoothly. I will only visit a health facility if I experience discomfort. Otherwise, what new things will the healthcare providers make for us if the pregnancy goes well? They simply examine us and tell us that we can return home if the pregnancy is going well. There is no need, therefore, to go to the antenatal care visit if a woman is well” [19].

Fear of being treated poorly by healthcare providers

The fear of being treated poorly by healthcare providers was found to have an impact on women’s access to maternal healthcare in 13 studies [12, 23, 25, 26, 30, 51, 55, 64, 65, 67, 87, 90, 103]. This fear resulted in women either completely avoiding care or delaying care-seeking until the later stages of pregnancy, childbirth, or the postpartum period. A study conducted in Southern Ethiopia, reporting the perspectives of pregnant women and healthcare providers, showed that a mother who had consistently attended ANC sessions at a health facility ended up delivering at home due to her fear of being treated poorly by healthcare providers [103].

“I was fine with antenatal care services provided but I have a concern about the way health care professionals treated my elder sister last year. During the time I was accompanied by my sister during labor and delivery, I remember that while my sister suffered from the pain of the labor the midwives and students in the room were not supporting or showing sympathy as our traditional birth attendants do.” [Para I, age 20, delivered at home, FGD 2] [103].

Past negative experiences

Past negative experiences with maternal healthcare services were found to impede access to the maternal healthcare in 11 studies [14, 15, 19, 21, 30, 34, 35, 61, 64, 77, 82]. A study in northern Ethiopia showed that homeless women who had received maternal healthcare in their last pregnancy cited barriers like long wait times, poor communication, uncomfortable examinations, and discrimination [64].

“During my first pregnancy, I experienced severe abdominal pain and cramps, and my relatives approached me to go to the hospital. The health care provider also advised me to take medications only, and they informed me to come back when my labor starts. Lately, I realized that I was actually in true labor and forced to deliver and my child died. That experience eroded my confidence and trust in health professionals as a result of which I decided to deliver at the open house for my recent child.” [HW010: a divorced homeless woman] [64].

Financial constraints

Eighteen studies showed that financial constraints impacted an individual’s ability to access appropriate maternal healthcare [12, 17, 23, 30, 32, 36, 37, 49, 52, 64, 73, 77, 87, 88, 91, 92, 100, 101]. These studies highlighted how economic barriers can prevent women from being able to afford regular prenatal check-ups, testing, ultrasounds, and transportation to healthcare facilities. Furthermore, these studies emphasized that women’s reliance on others for financial support further complicates their ability to prepare for childbirth and seek facility care. Due to financial constraints, many women encounter difficulties in preparing for childbirth, covering transportation costs, and meeting other essential birthing needs.

“There is a difference between poor and rich in utilizing institutional delivery; even in the absence of an ambulance, using a local ambulance was a challenge in that no one carries a pregnant poor family. In the presence of money sky is a way.” [a 47-year-old participant’s husband who has 8 children] [73].

The burden of domestic work

Nine studies indicated that the burden of women’s domestic workload affected their access to the maternal healthcare [17, 20, 34, 36, 51, 63, 66, 78, 99]. These studies highlighted the significant impact that household responsibilities can have on women’s ability to seek and receive comprehensive maternal health services. When women are overwhelmed by domestic tasks, it may limit their time and energy to seek necessary medical care during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum periods. A study conducted in the pastoralist region of Ethiopia found that women mainly prioritize looking after their children and family members at the expense of their health [34].

“Most women are busy with household activities such as cooking, feeding, cleaning, and caring for family members. Hence, they have no time to attend the awareness creation meetings organized by the health extension workers.” [FGD with women, Gorodola] [34].

Interpersonal level barriers (n = 31)

Limited family support

Of the 31 studies reporting interpersonal level barriers, 10 reported limited family support [12, 17, 18, 23, 34, 37, 63, 64, 78, 99]. Without adequate support, women may remain at home rather than seek maternal care, often due to a lack of encouragement and assistance from family and friends to utilize services. A study from Uganda revealed that while husbands are expected to attend the first ANC visit, participants struggled to involve and support them, as noted by one participant:

“When she [participant] wants to go for ANC at the health center, she will first ask her husband. Then the husband says, I’m not the one who is pregnant, so you have to go alone.” (ANC non-user, 26 years) [18].

Social influence

The negative influence of social networks was found to hinder women’s access to maternal health services in 11 studies [17, 19, 20, 25, 26, 30, 64, 69, 75, 78, 103]. Social networks can disseminate incorrect information about maternal health services, share negative experiences, and discourage seeking maternal health services, which may lead others to avoid visiting healthcare facilities. In this context, a lactating mother from a rural community in West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia explained the influence of social networks as follows:

“…Particularly, mothers and fathers-in-law, husbands, and the community influenced parturient women to spend some time in their homes encouraging them to deliver at home. This has caused delays for women interested in visiting the health centre, from visiting the facility.” [A lactating mother from Zalema kebele] [25].

Communication challenges with healthcare providers

Nine studies showed that communication or language barriers with healthcare providers impede women’s access to maternal healthcare [13, 17, 21, 27, 57, 76, 79, 93, 102]. These barriers can inhibit effective interactions and lead to misunderstandings and feelings of dissatisfaction. An 18-year-old first-time pregnant woman from a pastoralist community in Kenya traveled more than 20 km for antenatal care but found the information from providers insufficient and unclear, resulting in her dissatisfaction:

“All she asks is how many months is your pregnancy…then you are told to go home, she needs to tell us more, something more different… or what, going all the way, look how far our village is. Yeah, … she put something on her ear and my stomach saying she was listening to the baby breathing, then gave me some tablets, which she said would help my body, checked my ‘kilo’ (weight), tied my arm with that thing, but did not tell you why. She told me my height was small and baby big, but didn’t tell me anything more… she wrote in this book… then, said go home, nothing else.” [Midino 18 years] [13].

Lack of decision-making autonomy

Eleven studies indicated that women’s restricted decision-making autonomy, driven by cultural norms favoring male authority, economic constraints like poverty, and political limitations on reproductive rights, affected their access to maternal health services [27, 34, 37, 56, 60, 63, 77, 78, 87, 100, 103]. In rural Tanzania, women faced challenges accessing maternal health services due to a lack of autonomy to make independent decisions, even when they wanted to seek care:

“Women can’t make decisions. Only a man makes decisions, I see this in my grandmothers, and my mother, for example when my grandfather wants to sell his farm and my grandmother refuses, he will still sell it. Women do not have any authority.” [Married Woman] [37].

Health facility level barriers (n = 63)

Poor quality of healthcare

Of the 63 studies reporting health facility-level barriers, 18 described poor quality health care provision at health facilities as a substantial impediment to women accessing maternal health services [12, 18, 20, 21, 25, 33, 35, 52, 65,66,67, 76, 77, 80, 82, 86, 100, 102]. Substandard healthcare during pregnancy and childbirth can be characterized by delayed treatment, lack of attention, and insufficient resources, potentially discouraging women from seeking care, as reported in many studies [20, 25, 76, 82, 102]. As one of the studies noted, a lactating mother from a rural community in Northwest Ethiopia shared her experience as follows:

“In my previous pregnancy, my labour started at dusk…I spent the whole night labouring and the next day, Sunday morning, my father took me to the health centre. He told the health worker that I was in labour and asked the health worker to provide maternity care for me. But, the health worker said that he was off duty that day. My father became angry and argued with him…Ever since, I have not been interested to visit the health centre because I believe that they can do nothing for me.” [A lactating mother from Kentefen kebele] [25].

Poor infrastructure and limited medical supplies

Poor health infrastructures were identified as barriers to accessing the maternal healthcare in 13 studies [13, 14, 36, 37, 51, 54, 57, 58, 85, 92, 99, 100, 102]. Additionally, the shortage of medical supplies, including sterile instruments, medications, and diagnostic tools, was reported to affect access to maternal healthcare services, as noted by 17 studies [13, 18, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 33, 34, 36, 54, 58, 76, 89, 99, 100, 102]. In one study, a healthcare provider at Defkela Health Center in Southwest Ethiopia shared the following:

“Lack of road access, distance, and landscape of the area are the known and evident challenges. I [care provider] know that mothers are coming to the health facilities fleeting all these challenges. However, we [care providers] lack supplies to provide them[mothers] with quality services that encourage them [Mothers] to return for more services. For example, currently, we [care provider] lack drugs, a blood pressure cuff, a weight scale, laboratory services, a functional maternity waiting home, electricity, and water supply… we [care providers] fetch water from a river using a donkey and or human power, which costs us 20 birrs for a jar containing 20 liters.” [Health care provider at Defkela Health center) [102].

Shortage of trained healthcare providers

Thirteen studies identified a shortage of trained healthcare providers as a barrier to accessing the maternal healthcare [14, 23, 24, 27, 53, 57, 59, 66, 74, 76, 88, 90, 101]. Additionally, 10 studies revealed concerns about inadequate provider competency as another barrier to accessing the maternal health services [21, 27, 29, 51, 64, 69, 85, 87, 88, 97]. As noted in a study conducted in Uganda, a 48-year-old refugee from the Nakivale Refugee Settlement explained:

“There was a day I accompanied a woman who was going to give birth [to the health facility]. There was only one nurse who was alone and already tired and she had to go and get lunch. But there was a woman who was already giving birth and she was shouting, “Doctor! Doctor!” So I entered and got some materials and when the nurse came in she asked if I was a nurse, I said yes. I could not see a woman suffering” [76].

Abusive behavior from healthcare providers

In 24 studies, abusive behavior from healthcare providers, such as being disrespectful or insensitive, was reported to hinder the maternal healthcare and lead women to feel discouraged from seeking necessary medical attention, attending prenatal appointments, or following recommended care protocols [15, 18, 23, 25, 29, 30, 32, 34, 36, 49, 53, 60, 64, 68, 74,75,76, 78, 85, 86, 95, 98,99,100]. As noted in a Ugandan study, a mother from the urban slums of Kampala explained:

“It is a government hospital but the health workers some of them are very rude. Now like when I was there, there is this woman, who was there, the health workers were not caring about her. I think by mistake her water broke when she was there; immediately the health worker who was on duty came, instead of taking her to labor suit, she pulled her hair and shouted at her, telling her that you are not supposed to deliver from there, abused her, yet she was the one not taking care of her. It is even us who called her, some of those health workers have no mercy, they talk to us rudely yes.” [IDI, mother, Makindye division] [100].

Distance to the health facilities

Distance to health facilities and a lack of transportation as an additional barrier. Seventeen studies reported that women in remote or underserved areas do not seek timely medical attention for the maternal healthcare due to the challenge of traveling long distances [16, 17, 23, 24, 28, 30, 32, 36, 51, 52, 60, 68, 72, 81, 96, 98, 102], and 20 studies reported a lack of transportation to reach facilities [14, 17, 20, 23,24,25, 28,29,30,31, 33, 37, 49, 51, 52, 85, 94, 99, 102, 103]. Both the lack of available ambulance services and the high traveling costs were reported as critical obstacles to maternal health services access [20, 28, 37, 49, 52, 94, 102]. As noted in a study conducted in Ethiopia, in which a religious leader from the pastoralist communities of the Ada’ar district in Afar explained:

“There are many mothers who do not go to a health facility for follow-up. The reason is the long travel distance. They are not able to reach it on foot. At the same time, they could not get a car. If they could not get a car, they could not go” [51].

Community level barriers (n = 37)

Socio-cultural norms

Of the 37 studies reporting community level barriers, 28 reported socio-cultural norms affecting women’s utilization to the maternal healthcare [12,13,14, 16, 18,19,20,21, 23, 25, 26, 28, 31, 49, 51, 61,62,63,64, 69, 72, 82, 88, 92, 96, 99, 102, 103]. These studies indicated that, in certain cultural settings, traditional practices are preferred to modern medical care, which puts pressure on women to seek assistance from untrained birth attendants [21, 25, 51, 69, 96, 103]. Additionally, studies noted that religious beliefs impact perceptions of maternal health services, as some communities may see hospital births as conflicting with their traditions or beliefs [12, 21, 68, 95, 98]. In one of the included studies, a 50-year-old married male FGD participant from the Digo community in Kwale, Kenya, shared his experience as follows:

“They [women] did not easily go to the hospital or clinics, furthermore when a woman got pregnant, she just stayed at home… and in case of any complications, there was always traditional means of treatment. Certain plants were used to relieve women of abdominal pains and it has taken long to change.” [Male FGD participant, 50 years, Married, 3 children, Magodzoni village] [69].

Societal stigmas

Societal stigmas significantly affect women’s access to the maternal healthcare, as indicated in six studies [18, 37, 55, 62, 75, 87]. These studies highlighted that societal stigma arises from negative perceptions of unplanned pregnancies, teen pregnancies, pregnancies outside of marriage, and the unfounded perception that women who attend an ANC clinic early in their pregnancy have HIV, and these stigmatizing beliefs prevent women from accessing care [37, 62, 87]. As one of the studies noted, a married woman from rural Tanzania shared her experience as follows:

“If you start clinic early and find that your health is weak, and neighbors seeing you going every month to the clinic say “this one is already infected with HIV, she has started taking medication” So you find many women are reluctant to start clinic early when the pregnancy is still young, but it is not advisable, pregnant women have to show early at the clinic to get their health checked.” [Married Woman] [37].

Policy level barriers (n = 13)

Lack of focus on maternal health in policy

Of the 13 studies reporting policy level barriers, 4 reported a lack of policy focus on maternal health services [29, 86, 89, 99]. These studies highlighted that a lack of policy focus can create barriers to accessing care related to, transportation, long distances to healthcare facilities, and limited availability of services like PNC [29, 89, 99]. As one of the studies noted, a health extension from a rural district of the Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia shared her experience as follows:

“As to me, PNC did not get attention like other health services even from the top government authorities involved in the health system. For example, when individuals from the health system visit health post to take reports, their main concern is the number of mothers who completed fourth ANC and facility delivery. They do not ask us about home based postnatal care. They only compile the reports that they think as a core. Surprisingly, we do not have a uniform known registration book for documenting postnatal home visit, rather what we do is document in a different piece of paper.” (30-39 years old HEW, FGD) [89].

Conflict and restrictive laws

Conflict and restrictive laws also severely hinder women’s access to maternal healthcare by destroying healthcare infrastructure, creating a shortage of trained professionals, and imposing unsafe travel conditions, as highlighted in eight studies [20, 54, 55, 58, 74, 80, 90, 99]. As one of study noted, a 26-year-old mother who delivered at home in the Amhara region of Ethiopia shared her experience as follows:

“…Political instability makes the situation to be worst especially for the lack of ambulance because the ambulance is assigned for the civil war activity. On the other hand, most of the women did not know their date of labor, sudden onset of labor, and restriction of transportation due to the civil war.” [26 years old home delivered mother, Amhara region] [99].

link